- Yazarlar

- 23 Sentyabr 2024 07:00

- 14 368

How does Armenia see its own and the future of the South Caucasus?

I carefully read the article by Grigor Atanesyan, an author of Armenian descent, titled “The Armenian Disaster: A Small Nation Chose War, Not Compromise.” Since the article was published on a platform like UnHerd, which is known for free-thinking individuals, it has sparked interest among many intellectuals in the Azerbaijani segment of social media. Arguments for and against the article have been voiced. However, the article, in which I share some of the theses and terminology, does not answer the main question: How does Mr. Atanesyan and the people he represents envision their own future and the future of the South Caucasus?

Let’s make the question more specific: Does Armenia and the Armenian society plan to adhere to the principle of uti possidetis juris under international law (i.e., accepting the borders that existed during the Soviet era), or do they intend to continue making territorial claims against neighboring states and live with the desire for revenge?

Any analysis that doesn’t provide a precise and comprehensive answer to this question is questionable in terms of objectivity and usefulness for peace. Appearing peaceful does not justify distorting the background, dynamics, and outcomes of the extremely complex conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia. Furthermore, utilizing the appealing term “compromise,” which promotes the peaceful resolution of any conflict through the norms of international law, to indirectly accuse Azerbaijan of xenophobia does not seem sincere either.

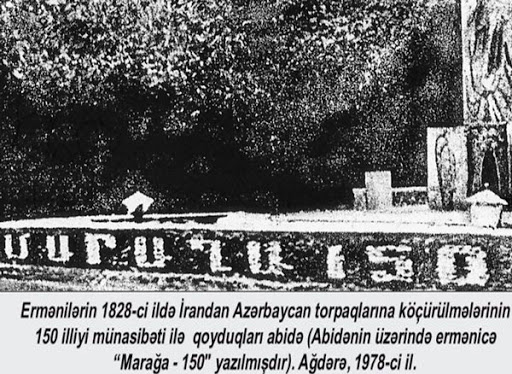

The author begins by stating that "for the first time in a millennium, there are no Armenians left in Nagorno-Karabakh." Unfortunately, this thesis reflects the ideological views of the chauvinism that has fueled Armenia’s territorial claims against Azerbaijan. We are now in the 21st century. In our time, positive scientific knowledge has been separate from religious institutions for several centuries. In the era of Auguste Comte, the founder of positivism (1798-1857), the Qajar Empire and Tsarist Russia were engaged in fierce competition for the territory of Karabakh, which belonged to the khans of the Javanshir tribe of Azerbaijani Turks. In 1828, the Treaty of Turkmenchay was signed between these two empires. Armenians were relocated to Karabakh from Iran based on the terms of that treaty. During the Soviet era, Armenians living in the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region, which was an integral (according to the constitutions of both the USSR and the Azerbaijan SSR) part of Azerbaijan, celebrated their migration history with great fanfare and even erected a monument in honor of their migration that took place 150 years prior.

Photo caption: The monument erected in 1978 in Nagorno-Karabakh in honor of the 150th anniversary of the Armenian migration to Karabakh

In 1836, Russian Tsar Nicholas I issued a decree subordinating the Apostolic Church of historical Caucasian Albania (which, by the way, was a dyophysite church) to the monophysite Armenian Church. Thanks to the Russian Tsar, the Armenian Echmiadzin Church established authority over a deep-rooted religious community with a history of nearly 1,500 years and attempted to erase its entire past. All these efforts were imposed on Armenian society as dogma, characteristic of religious ideologies. Any society that does not subject its ideological dogmas to the scrutiny of positive science and refuses to confront the true facts of history is destined to have a flawed vision of the future.

It is also unequivocally clear that the reasons for the Karabakh conflict that began in the late 1980s are far from what Grigor Atanesyan noted. On February 20, 1988, the Armenian deputies of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region, which was part of the Azerbaijan SSR, adopted a resolution to "join Armenia." That decision was later confirmed by the Supreme Soviet of the Armenian SSR. This was an open and unacceptable violation of the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan, a sovereign state within the USSR (even if only formally). As a result, these “decisions” were not recognized by the USSR either. After the fall of the "Red Empire," Azerbaijan, which gained independence, was admitted to the United Nations without its territorial integrity being questioned. In the following years, states and organizations referencing international law consistently emphasized that Karabakh was a sovereign territory of Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan and Armenia were admitted to the UN simultaneously. However, it was after this event that Armenia intensified its military aggression against Azerbaijan, expanding the borders of the "self-proclaimed republic" it had created and supported in Karabakh through a war of occupation.

In his article, Mr. Atanesyan highlights only the "tragedies of the Armenian people" without addressing Armenia's aggressive policies or the Azerbaijani territories it occupied. In my opinion, the main flaw of the article is that the author overlooks the legal, historical, and moral grounds for Azerbaijan's liberation of its lands from occupation. However, Armenia’s responsibility and the systemic obstacles it has posed to the peace process extend beyond just the occupied areas outside the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region of Azerbaijan. Yes, Azerbaijan endured 30 years of occupation. During the occupation, the residential areas of Karabakh were razed to the ground. Our natural resources were illegally exploited. Azerbaijanis, subjected to Armenia’s policy of ethnic cleansing, sought nothing but justice from the world during this period. As no one showed willingness to implement the four resolutions issued by the UN on this matter, Azerbaijan restored justice on its own. Now, considering the reasons for all these events as "mutual" and creating an artificial balance does not serve justice, truth, or peace. Such maneuvers are not much different from the excuses brought forward by Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan to avoid signing a peace agreement with Azerbaijan.

The Peace Treaty draft presented by official Baku to Armenia is based on the principles of international law. Today, Armenia’s Constitution contains explicit territorial claims against Azerbaijan and other regional countries. Any peace treaty is an international agreement, and international agreements do not have supremacy over the constitutions of either Azerbaijan or Armenia. Therefore, for sustainable peace to be achieved in the region, Armenia must completely abolish its domestic legal framework, which revanchist forces could reference. In response to Azerbaijan's proposal, the Prime Minister of Armenia claims that "international treaties are superior to laws." By doing so, the Armenian leader pretends not to know the difference between a constitution and laws. The reason is simple: Armenia, encouraged by some regional and global actors, intends to buy time and use the extended period to rearm.

Azerbaijan’s victory in the Karabakh war is an inevitable outcome. From economic, demographic, and modern perspectives, Azerbaijan is the leading country in the South Caucasus. Our capital, Baku, and our ally Georgia’s city of Batumi, create a historical and geopolitical paradigm in the region. The Dashnak mindset, which has failed to understand this paradigm, has led Armenia to disappointment. However, Armenia still has a chance to ensure the prompt opening of the route connecting mainland Azerbaijan with Nakhchivan (often referred to by experts as the "Zangezur Corridor"). This would mark a new chapter for both Armenia and the South Caucasus. To demonstrate such political will, one only needs to look at the path taken by the Baltic states over the past 30 years. The experiences of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia show once again that the countries of the South Caucasus must invest in people, not in arms. For this very reason, most Azerbaijani political analysts are eagerly awaiting the emergence of Armenian thought that seeks to answer the question, "How modern are we?" rather than "How ancient are we?" So far, such a trend is not visible in Armenia.

Armenia seeks to share the blame for its defeat in the Second Karabakh War. Similarly, it does not want to be an independent counterpart to Azerbaijan, which aims to bring peace to the region with the new reality it has created. Once again, Armenia looks for intermediaries and patrons. However, experience has shown that peace cannot be delivered to regions like the South Caucasus, where global powers' interests clash, through the mediation of patronage institutions. As American philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson famously said: "Nobody can bring you peace but yourself."

Taleh Shahsuvarly

About the Author: Taleh Shahsuvarly was born on March 10, 1977, in the Karabakh region of Azerbaijan, in the Barda district. He graduated with bachelor's and master's degrees in the history of philosophy from Baku State University. Later, he pursued higher education in law at the same university. He participated in the Second Karabakh War as an officer with the rank of "senior lieutenant." Shahsuvarly is a political analyst. After completing his higher education, he engaged in journalism in Azerbaijan. Since 2018, he has been the editor-in-chief of the analytical-information portal AzNews.az.